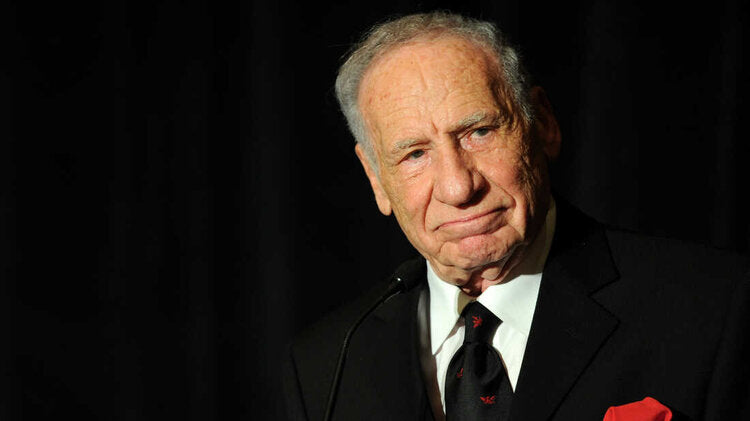

The quest continues. Even after over 70 years in the business of show, the 95 year old comedy giant – standing at 5 foot 5 – named Mel Brooks is on the front lines, searching far and wide for one thing and one thing only: The ultimate joke.

“Something that is very important to comedy writers. Information,” Mel Brooks told us over the phone a few weeks ago, giving us full insight into just how the comedy portion of his brain works. “It won’t explode into a comedy moment unless the audience is armed with a bunch of information. With valleys of information, there are no peaks of comedy. And I set it up with plenty of information.”

As much as comedy is subjective, there’s a very good chance that Mel Brooks has broken through that at some point during his career. There’s an absolute relentlessness to his work that you can’t help but break out laughing. As he says it “I throw twenty jokes out hoping to get a laugh with two or three of them.” That’s one of comedy’s not-so-well-kept secrets. Never giving up. If a joke doesn’t work, try again on the next one. Maybe you’ll have better luck.

Mel Brooks shows no sign of stopping. Last month, it was announced that he will co-write and produce a History of the World Part II series for Hulu. And today, Brooks is releasing his autobiography, All About Me. In it, he shares all the tales from a storied career – from his days growing up in Brooklyn to working on Your Show of Shows to making some of the greatest comedy films of all-time to the 2000 Year Old Man to bringing The Producers to Broadway and beyond. Even at 450 pages, it’s clear there’s still way more left to come from the mind of Mel Brooks.

We spoke with the comedy icon about the process of writing the book, the things he forgot about, the worst he ever bombed on stage, the controversy that still surrounds Blazing Saddles, working with fellow comedy heavyweights like Jerry Lewis, Johnny Carson, Richard Pryor, and Dick Shawn, why he never made a movie with Carl Reiner during their 70 year friendship, and why history will never not be funny.

Thank you so much for doing this.

You did a very good job [writing an article for another publication about] The Twelve Chairs, breaking that down, analyzing it, and connecting music to comedy. It was wonderful. I just loved your article. Very, very well done.

Wow! Thank you! That means a lot to me. It’s a pleasure to connect with you again. I just read the book…

So you’re talking about my autobiography, right?

Yes.

Yeah! Well the trouble I had was there was too much of it. I mean, I’m 95. There’s just too much autobiography to tell. It would be as fat as the encyclopedia of botanical. I had to be very choosy in remembering stuff that was not only interesting but entertaining. And still stick to the story of my life. So it was not easy. But I just picked out the things that I enjoyed doing in my life.

Chronologically I went from being a little boy in Williamsburg, Brooklyn to a soldier in World War II, to Broadway, to being an assistant to a devilish, wonderful man who taught me everything right and wrong about Broadway, to finally being a moviemaker, and eventually getting back to Broadway, my first love. So a lot of adventure. A lot of adventure.

There is indeed a lot of adventure here. And I’ve got to ask, how long has this been in the works? Have you thought about doing a memoir like this for a while? Did it just come up?

Well, my son Max, who is a good writer in his own right of Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z. He’s just a wonderful writer. He said “What’re you going to do? There’s a pandemic. You can’t go out. You’re afraid to be besieged by autograph seekers who might give you COVID. So since you’re stuck in the house and you don’t know what to do with yourself, this would be a good time to write – eventually you’ve got to write – your life stories.” So he proposed it, he got his agent – a guy in England, Johnny Geller – and I was off writing it.

And through the process of it, did you find yourself remembering things that you had long forgotten? Did that spark up some distant memories? Because I’m always fascinated with that process of reflection.

Absolutely! Things that I hadn’t thought of for literally 50 or 60 years. Completely forgotten. For instance, as a 19 year-old soldier, going to the mess hall dining room, and looking at something being put on my plate and asking “What was that??” And the soldier next to me said “That’s called sh*t on a shingle.” “What’re you talking about??” Turns out it’s creamed beef on toast. But it does look a lot like sh*t on a shingle.

Things like that that I just completely forgot. Just amazing! Stories of being 5 years old remembering my oldest brother… I’m the youngest of four boys. And next to me is Bernie and then next is Lenny and then the next is Irving. And I remember one Christmas Irving found an old broken sled, fixed it up, polished the runners, put me on it, took me around the block, and he had taken me 20 times. And I said “Irving, please, one more!” And I remember he said “Okay.” And he pulled me for 21 around the block in Brooklyn. I completely had forgotten about being pulled around the block on a sled that he had fixed. Stuff like that. It had all come back. Just wonderful memories.

My mother, on very cold winter mornings – we only had a couple of radiators in the tenement in Brooklyn – she was just so wonderful. She was a great woman. She took my clothes that I was going to wear to go to kindergarten and she put them on the radiator and warmed them up and then dressed me. She used to dress me under the covers, so when I popped out of bed, I was warm. So on a cold winter morning, I was warm, because she kept the clothes all warm. It all came rushing back. Things like that, they came rushing back to me. Storied feelings.

Being run over by a tin Lizzie doing an eagle turn on my skates that little turn and then boom! Down! And a wheel [came] over my belly. I thought I was dead. I remember saying “Goodbye cruel world!” I think I was 5 or 6. Actually, I was 9. And then my brother Irving taking me to St. Catherine’s Hospital. And then a nun, who looked like a big penguin, came over with a big, heavy cross dangling on a chain, and she said “You have to urinate in this.” And I said “I don’t know…” She said “You have to PEE in THIS!” I said “I can’t pee.” And she said “If you don’t pee, we’ll go into your pee-pee and get the pee out.” And I said “Gimme that!” It turned out that little kids, 8 or 9, have rubber bellies, especially if it’s a tin Lizzie that runs over them. Stuff like that. Completely forgot! It’s all in the book.

I love that! One thing I loved reading about in the book is your days working in the Catskills mountains doing comedy. Do you recall the worst you ever bombed onstage?

Yeah, I do. I remember, it was like the first or second time [I was onstage]. It was at the Butler Lodge. I was the drummer. And the comic got sick, so I used his material. And he had a knack of delivering it that I didn’t have. And at the end, I got maybe one or two people applauding. It was just dismal. I said “Okay. I’m not a performer.” And then, when I did it again, I didn’t do his material. I made up my own material, which I understood and related to the audience. And I made up my own comic jokes. And suddenly from no applause to standing ovations. I said “Okay. I can leave the drums and go into show business.”

You’ve always said that rhythm is an integral part of doing comedy, and knowing it all beat by beat.

Absolutely. And the thing is, when you write your own material, it resonates. It’s always true. You’re not Henny Youngman doing jokes like “My wife says ‘You never take me anywhere. I never go anywhere. You never show me anything new.’ So I took her to the kitchen.” Good jokes, but one liners that had no soul or no heart. Just jokes.

That’s some great advice. There’s gonna be a lot of jumping around, because there’s so much I want to ask you about. In the book, you talk about working with Jerry Lewis briefly as a writer on The Ladies Man. You mention you two had creative differences, yet I consider you both as two of the great comedy filmmakers of that time period who mastered capturing visual gags. What was the disconnect?

Well, Jerry liked to be super in charge of everything. Including the comedy. But the comedy has to be written. It has to be made up. It was The Ladies Man. He was a janitor and episodes had to be kind of natural. And he was just looking for big laughs. The kind of jokes that I wrote in that movie were he’d be cleaning butterflies under glass. And he lifted the glass and they all flew away. It was just crazy. And he said “That couldn’t happen.” And I said “I know! That’s what makes it funny!” So we had fights like that about the butterfly. I wrote a joke about falling asleep in a convertible going through a car wash and his knee pushes a button and the top opens and he’s just drenched. He liked that.

I couldn’t get enough of my own stuff in, because he’s a pretty good comedy writer himself and he wanted to be in charge of everything. And I learned when I made my own movies “Get as much help as you can. You cannot be in charge of everything. There’s somebody that has to light you, somebody has to photograph you, somebody has to come up with a storyline.” It’s collaboration. Movies are an incredibly collaborative medium. And Jerry didn’t appreciate that. “No collaboration. Me generalissimo. Me boss. You listen. Take notes.” No. We, too, are creative. We the writers. We had fights every day.

Anyway, but later, when I was making my own movies and he was making his, he realized that Mel Brooks was not just a stooge but he was a talent in his own right. Then we became good pals. He kept saying one thing. Contemporaries usually have little spats about who’s got the better this or that. And the one thing Jerry would come at me with “They like you in France but they love me in France.”

And that’s something I love because, after your second film The Twelve Chairs, wasn’t that the last movie you wrote all by yourself before adopting the writer’s room principal?

Yeah. Well actually, History of the World was the last picture I wrote all by myself. And it was big. But it was in different areas. So it was like four small movies. I could write a small movie. I didn’t need any help. So I write small movies and called it History of the World Part I. I even came up with coming attractions of Hitler on Ice, Jews in Space, crazy stuff like that. I was just insane.

I’m a big fan of History of the World. But probably my favorite movie of yours is The Producers. And one person that has always fascinated me is Dick Shawn. What was he like to work with?

I don’t use the word genius frequently, but I would say that Dick Shawn was a bit of a genius. He had crazy ideas coupled with incredible energy and a happy disposition. Great, happy sense of humor. He just charged up the set with joy every time. He played his hippie against Eva Braun and said “Don’t bug me, baby. I gotta conquer France.” It was so insane. He decided to do a kind of hippie. I had written a different kind of character, but he turned it into a kind of banana skin eating whacko. He was so original. So original. So great. I loved working with him.

It’s such an incredible performance. And over the scope of your career, is there a gag or a joke or even a film that you feel is terribly underrated?

Well you took the world to task for not recognizing and celebrating The Twelve Chairs as much as it should have been. And I agree with you 100 percent. That’s the one movie that I didn’t think I was writing a little art movie that could never cross the George Washington Bridge and get into the country. But it turns out that the world saw it as a little kind of foreign movie or a little art movie. And it was a simple, wonderful story. A human drama.But I guess that the history or geography that went into it was a little too foreign for audiences. It was what happened in Russia during and after the Russian Revolution in 1917. So I just assumed that a lot of people knew there was such a thing. But I realized later I needed a lot more education up front in that movie for it to work as beautifully as I thought it should.

And then your next film, of course, was Blazing Saddles, which remains a controversial film all these years later. Are you surprised that it is still so taboo in 2021?

I am a little. I am. Blazing Saddles is really kind of anarchy. It just breaks all the rules. I didn’t know enough not to use the N-word. But I hard Richard Pryor – and myself and some other writers – he used the N-word just as normal talk. Had Richard not been there, I don’t think I would have had the nerve to use it, even though it was not so politically incorrect then as it turned out to be. I’m lucky that Richard was there, as Richard Pryor was a bit of a genius again. He was the most talented guy.

And I thought he was going to play Black Bart. And Warner Brothers said “No. He’s been arrested for drugs too often. We can’t have insurance.” And I was not going to do the movie and then Richard said “Come on! Mel, together let’s find a good black sherif.” And we did. We went to Broadway and we found Cleavon Little who was so handsome and brilliant and funny. And Richard Pryor said “We took a good bounce. We took a good bounce, Mel. We got a better Black Bart than I could’ve played. I still don’t believe him to this day, but he knew his stuff. And we both fell in love with Cleavon. So that worked out beautifully.

It absolutely did. I think the film holds up so well. Another cool thing you got to do in your illustrious career is that you were on the very first Tonight Show that was hosted by Johnny Carson. What do you remember about that night and how did you see him evolve over your subsequent appearances?

You know, I fell in love with Johnny Carson the minute I met him. Because he was a good natural audience. Other night time hosts – I can’t blame them – they always wanted a few laughs for themselves. And they weren’t such good audiences as they were sometimes competing with you for the audibles attention and laughs. Carson was a natural, beautiful audience. He just listened.

And one of the first things I did, I think on the first show, is I played an Indian ichthyologist. I played an Indian professor of fish and mostly about sharks. And I said stuff like “If somebody rings a bell and you don’t get a clear answer, it might be a shark. Don’t let him up into your apartment.” He just left the desk, hit the floor, grabbed his belly, and started screaming. Nobody like Johnny Carson. Great audience.

And we’ll never see another like him. As I was prepping for this interview, I stumbled upon something interesting. Over your 70 year friendship with Carl Reiner – during which you two did the 2000 Year Old Man -, he never appeared in one of your movies and vice versa, save for him being the voice of God in History of the World Part I. How did a crossover never happen?

It’s a wonderful mystery. I don’t know. I never used Carl because I had found somebody who did that kind of thing brilliantly for me and that was Harvey Korman. And Carl never needed me because he always found brilliant people like Steve Martin to work with in movies. I don’t know. It just worked out [that way]. When it wasn’t movies, Carl and I were the best. When we had to do live shows and stuff and the 2000 Year Old Man. But I don’t know. When it came to movies, he had his core of wonderful funny people like Lily Tomlin, etc., wonderful acting people. And I had mine. I had Madeline Kahn, I had Cloris Leachman, I had Dom Deluise. I was rich in movie talent.

But I’ll tell you what we did do for each other. [We watched] a rough cut of each movie. He saw a rough cut of mine and I saw a rough cut of his movies. And I’d give him a couple of pages of notes where I thought it could be improved or something didn’t work as well. And he did the same for me. So we polished each other’s movies. But we were not physically in them.

I love that. You two had such incredible chemistry. But it is a shame we never got a 2000 Year Old Man movie.

I miss Carl very much. Carl and I used to watch things like Jeopardy! together and compete at answering questions and stuff like that. He lived on Rodeo Drive. And I miss so much, I miss all the nights of coming over, having dinner with Carl. Sometimes incredible dinners like stuffed cabbage and stuff you can’t get anywhere in the world except Carl’s. Or sometimes he’d have bratwurst on frankfurter rolls with mustard and sauerkraut. Crazy. Carl always liked different, wonderful stuff.

And also, he was great in real life. Not just onstage. One night we did [a joke with] a cigar band with just the two of us, no audience. We broke each other up until we couldn’t laugh anymore. Because I kept saying “It’s so beautiful. That’s the most beautiful ring.” It’s a cigar band! Me and Carl and a cigar band. Alone. No audience. And he would say “It’s a cigar band!” And I would say “Yeah! But look at it. Doesn’t it look like a ring?” (Laughs). And I’d pummel him. “I think it is a ring!” And he’d say “It’s a cigar band!!”. Nobody in the world but the cigar band and Carl and myself. And we loved and respected comedy so much that we just did it for ourselves.

That’s so beautiful. And my sincere condolences on the loss of Carl. I was fortunate to get to speak with him twice.

Aw yeah. It’s like Billy Wilder said that William Wyler and he had come from [Ernst] Lubitsch’s funeral. And Billy Wilder said to Wyler “Oh how terrible. No more Lubitsch.” And Wyler said “Worse than that.” And Billy said “What could be worse than that?” And Wyler said “No more Lubitsch pictures.” (Laughs). Stuff like that is so, so precious.

Absolutely it is. I love that story. The final question I have is, the last chapter of your book is titled The Third Act. And now you’re working on History of the World Part II for Hulu, meaning there’s going to be a fourth act before the book even comes out. It’s great! And I have to ask, is it surreal to helm something like this all these years later, at this point in your life?

You know, for me it’s natural. For others, it is surreal. Definitely surreal. And it makes sense that it’s surreal. But it’s just a progression of searching for that elusive or brilliant comedy sketch or joke. I never stopped searching for the ultimate joke or the ultimate laugh. I keep lookin. I keep doing it. I enjoy the search.

And I cannot wait to see the show next year.

Yeah well history never stops! History never stops. It’s always making more history. And it happens every day. If we just went and got old newspaper headlines, we’d find a lot of stuff that they thought in those days was important. But we could even see World War I as some kind of comedy now. It’s so bizarre. Why it started. Why they wore pointy helmets. Things that were serious find themselves to be funny when they’re looked at later, with a latter point of view. Why did they wear those?? What, did they think they were going to run into each other with those pointy helmets? It’s funny. I mean the whole nation going to war with pointy helmets. It’s just funny. So history is always going to be funny.

Just like Mel Brooks.

Well, bless you. You know, I throw twenty jokes out hoping to get a laugh with two or three of them.

Mel Brooks: All About Me is available now wherever you get your books.